In a healthy body, millions of new cells are produced every day to replace the old ones. The so-called stem cells are responsible for this by dividing. Some of their offspring take over certain functions in the tissue, while others, as stem cells, ensure continuous renewal. This process takes place particularly quickly in the intestine. Its epithelium, the wafer-thin layer of cells that covers the intestinal wall, renews itself every four to seven days. If this process is disturbed, it can lead to serious diseases such as cancer. A prerequisite for possible therapeutic approaches is to understand exactly how the renewal process works. A team of scientists from European universities and research centres with participation from the University of Graz has now discovered a previously unknown mechanism of stem cell regulation in the intestine, which was published in the renowned scientific journal Nature.

Only a few make the grade

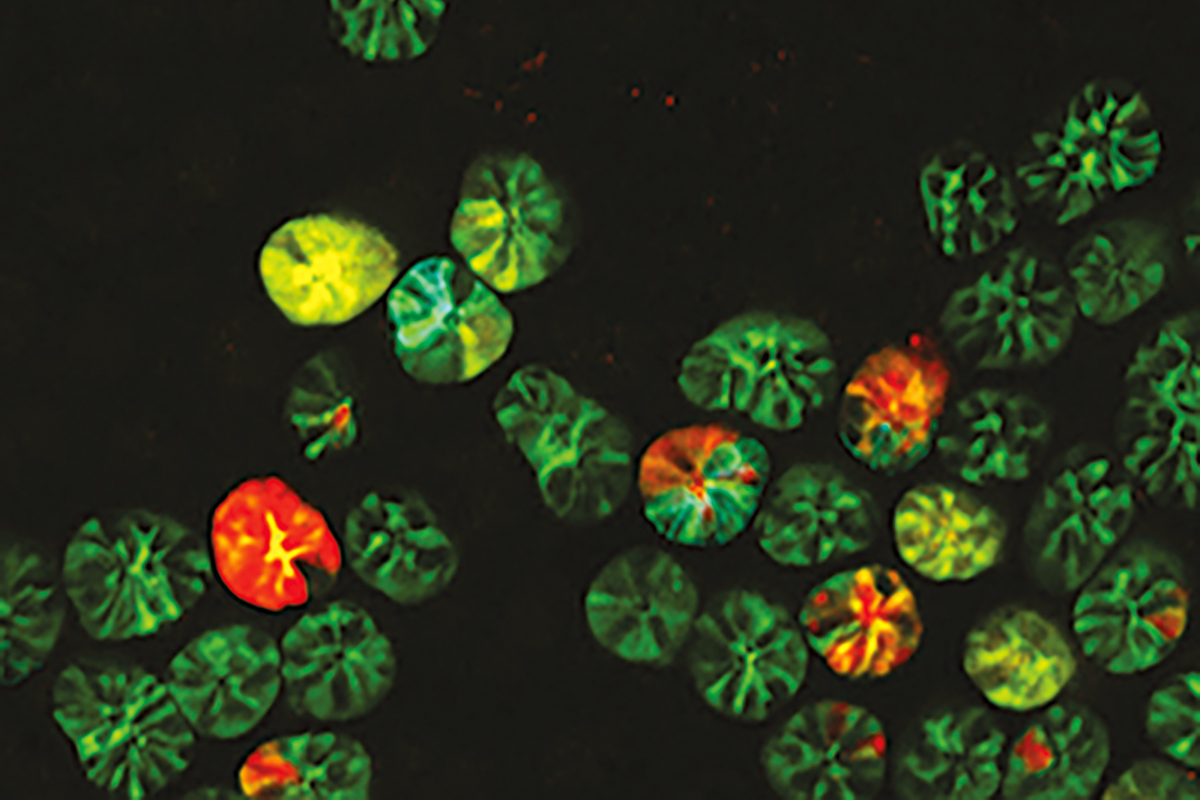

Stem cells can normally be recognised by their genetic profile and biochemical properties. "In our research, we discovered that there are many cells in the gut that would have the potential to function as stem cells based on these characteristics. At the same time, however, we observed that only a few of them actually fulfil this task and drive the renewal process. The rest are lost," reports Bernat Corominas Murtra from the Institute of Biology at the University of Graz, one of the first authors of the current study. The scientists were able to determine differences between the small and large intestine: "Although approximately the same number of potential stem cells is produced in both sections, many more are lost in the large intestine than in the small intestine," adds the researcher.

Movement makes the difference

In addition, the potential stem cells move differently depending on the section. "While they seem to move back and forth chaotically in the small intestine, the process in the large intestine is comparatively orderly," says Corominas Murtra. Responsible for the respective movement patterns is a biochemical signal that occurs much more frequently in the small intestine, the authors of the study found.

To answer the question of which factors influence stem cell regulation, the entire process was simulated on the computer using mathematical modelling methods. In the process, the researchers discovered a previously unknown mechanism: "From the movement pattern in combination with the geometry of the organ, it is possible to predict which cells are lost and which or how many remain as effective stem cells," Corominas Murtra summarises. This is the first time it has been demonstrated that the function of stem cells is not only dependent on their genetic profile.

These findings open up new insights into possible causes for malfunctions in one of the key organs of our body and provide a basis for further research into innovative therapeutic approaches.

Bernat Corominas Murtra was appointed professor for Complex Adaptive Systems in the Field of Excellence COLIBRI (Complexity of LIfe in Basic Research and Innovation) at the University of Graz in 2021.

Publication

Retrograde movements determine effective stem cell numbers in the intestine

M. Azkanaz, B. Corominas-Murtra et al.

Nature, DOI: 10.1038/s41586-022-04962-0